Made for

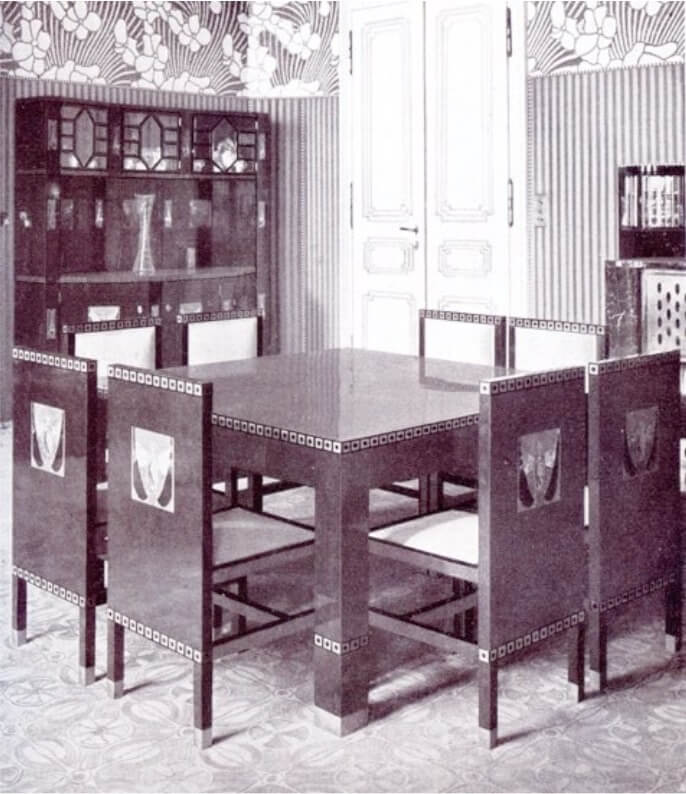

The Dining Room of Dr. Hans and Gerta Eisler Von Terramare’s apartment

Year

1902/03

Material

Burr elm veneered, snakewood veneered, birdseye maple veneered, Mother-of-Pearl and various types of woods

Dimensions

H. 94 x W. 47 x D. 50 cm

Koloman Moser, Designing Modern Vienna ; 1897-1907, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2013 – 2013

Koloman Moser, The Museum Of Fine Arts, Houston, 2013 – 2014

Zuckerkandl, B., « Kolo Moser » In Dekorative Kunst, 1904, No. 12, P. 329-354

Pichler, G., « Kolo Moser’s “Wohnung Für Ein Junges Paar” – Gerta Und Dr. Hans Eisler Von Terramare» In Leopold, R. & Pichler, G. (Eds), Koloman Moser 1868-1918, Prestel, Munich, London, New-York, 2007, P. 175-187

Fahr-Becker, G., Wiener Werkstätte – 1903-1932, Taschen, Cologne, 1995, P. 111

Rennhofer, M., Koloman Moser – Leben Und Werk – 1868- 1918, Verlag Christian Brandstätter, Vienna, 2002, P. 169

Koloman Moser, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2013, P. 127

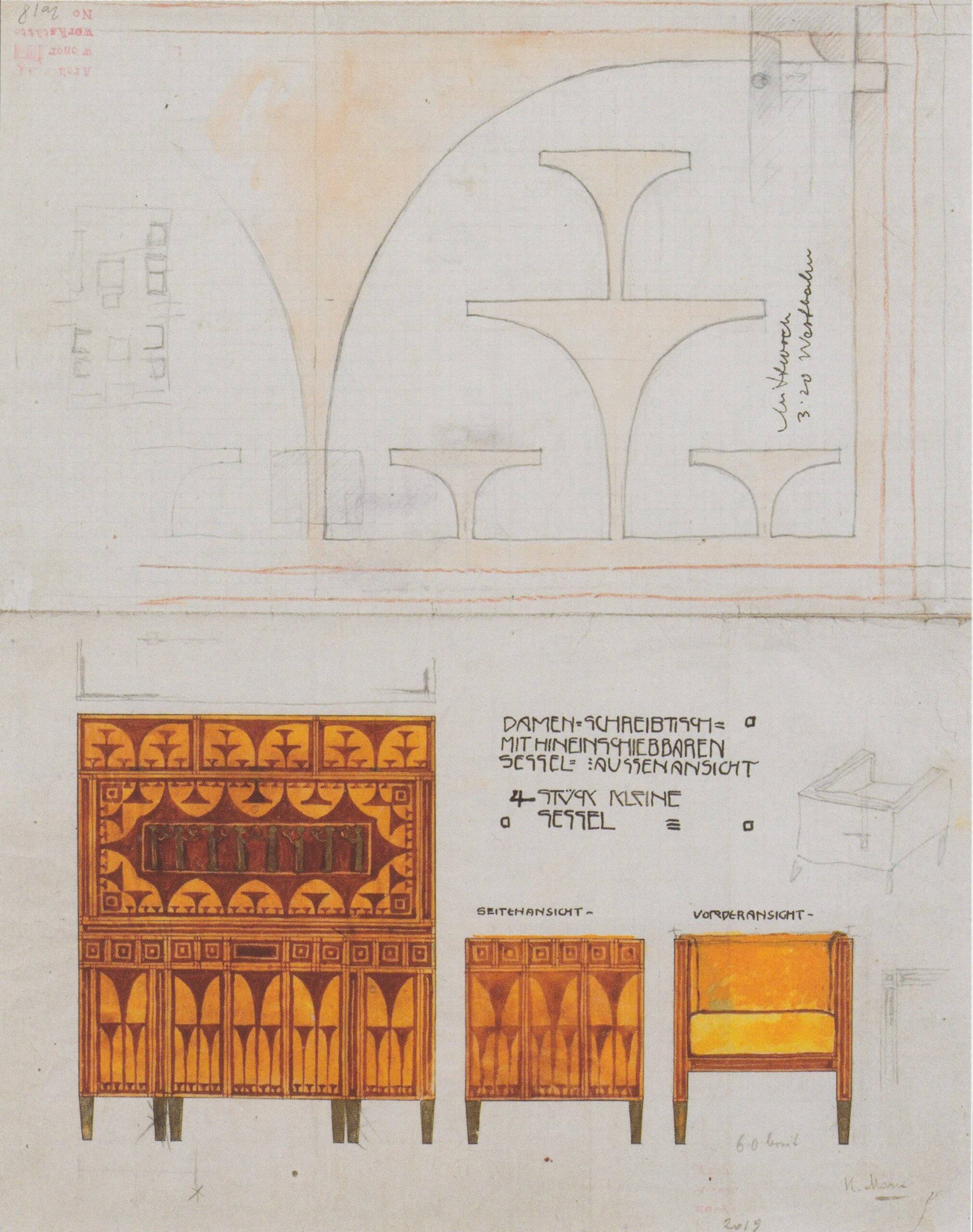

With the publication of Koloman Moser’s “Einrichtung Für Ein Junges Ehepaar” (interior for a young married couple) in the german art periodical “Dekorative Kunst” in 1904 the Viennese journalist and vehement advocate of the Secession Berta Zuckerkandl highlights Moser’s leading role in the development of modern Viennese language of forms. The feature that pointed the way to the future for her was Moser’s rejection of floral, curvilinear art nouveau, (Jugendstil), which still remained the model for the Vienna Secessionists until the late 1890s. Moser counteracts this new linear idiom – which she characterises as “tending towards the painterly” – with an abstract- geometrical style, tectonically oriented and constructed out of the square. At the same time she recognises its source in architecture and aspiration towards monumentality, which perforce must be the starting point for an interior design concept oriented on the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art. With this in mind, she leads us through the entire apartment, where the present chair found its place in the dining room.

Koloman Moser (1868-1918), who trained as a painter at the Vienna academy and school of decorative arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) and in the late 1890s worked in Otto Wagner’s architectural bureau, was one of the founding members of the Vienna secession. As such he was an exponent of the unity of “high” art and the “minor” arts, which had been inspired by the british arts & crafts movement and formed the basis for the Gesamtkunstwerk idea. The “interior for a married couple” represents Moser’s realisation of an interior design project as a total work of art, certainly his financially most exorbitant and his artistically most ambitious.

… It marks the initiation of a new geometrical-abstract language of forms in Vienna, to which Moser however, because of his training in the fine arts, adds his own distinct and independent flair…

He planned it in the crucial year of 1902, just one year before the founding of the Wiener Werkstätte. Its success combined with a number of interior designs and utility objects realised in the new abstract, geometrical language of forms made in and after 1901 encouraged Josef Hoffmann and Moser in the need to create a production base that would be independent of external compromise in quality. With the founding of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, they finally established the conditions for a production, carried out in direct contact with their clients and their executing craftsmen, which allowed them an uncompromising implementation of their creative ideas in realising a modern Gesamtkunstwerk.

This kind of overall concept for home living, in which every detail of the interior decoration and furnishings was produced by the hand of an artist or architect, needed a corresponding clientele. The latter firstly had to have abundant financial means at its disposal and secondly be prepared to subject itself to the artistic dictates of a designer. The search for new forms of prestige among the assimilated society of the Viennese Jewish Haute-bourgeoisie and the so-called “Zweite Gesellschaft”, the newly ennobled class, provided the secessionists with their ideal patrons. This was the background that also produced the “interior for a married couple” on commission of the physician dr. Hans Eisler Von Terramare, as Gerd Pichler has recently identified. He was the grandson of the industrial magnate Ignaz Eisler, founder of the largest tinned food and soup extract factory in the austrian- hungarian monarchy. On the occasion of his coming marriage to Gerta Loew, the daughter of dr. Anton Loew, the director and owner of the prestigious Loew sanatorium in Vienna, in 1902 Eisler von Terramare

Rented an apartment in Vienna 1, Schottengasse 10 at the corner of Schottenring and commissioned Moser for the complete interior design and furnishings. In the same year Klimt painted his portrait of Gerta Loew. Moser planned a vestibule, a living room, a breakfast room, a dressing room, a bedroom, a cloakroom, a kitchen, a servants’ room as well as the overall design and furnishings of the dining room, where this chair once stood. While keeping the windows and leaved doors from the time the house was built (1870), Moser created a completely new ambience by aesthetically reinterpreting the floor and of the wall and ceiling areas.

They are no longer simply a neutral background for the Moveables, but are made into a spatial capsule, autonomous, strong, and clearly defining the room in its tectonics. To do this he assigns a new architectural role to the wall and ceiling areas. He removes the original historicist stucco decoration from the ceiling, replacing its smooth plaster with white roughcast. By applying a golden, floral, curvilinear and stencilled petal pattern to the ceiling and drawing it down over a third of the wall area he fuses the ceiling into the walls. Underneath the petal pattern the walls are covered with vertically striped yellow silk and framed in their individual sections with square- patterned borders. The former parquet floor is carpeted and shows a yellow and brown pattern on grey ground. All furnishings standing in front of the wall or connected to it, such as the fireplace crowned with mirror and framed with glass cabinets, are of the same height and end shortly before the silk wall covering. The furnishings harmonise in colour with the overall character of the room through the use of reddish-brown exotic wood with marquetry bands of bright satinwood, abstract pictorial marquetry of mother-of-pearl and various types of wood, and gold-coloured metal mounts.

The form and tectonics of the dining-room furnishings recall Moser’s sideboard “der Reiche Fischzug” (the rich haul of fish), shown already in 1900 in the viii secession exhibition and extended in the same year into a dining-room design for the Zuckerkandl family. It marks the initiation of a new geometrical-abstract language of forms in Vienna, to which Moser however, because of his training in the fine arts, adds his own distinct and independent flair. It results from the combination of clear tectonic elements, but which are frequently used atectonically.

On contemporary photos of the dining room it becomes clear that Moser doesn’t design the chair independently from the dining-room table, but sees the chair in spatial unity with it. The dining table group becomes a room within a room, so to speak. The transparent volume of the table is encapsulated by the closed walls of the chair backrests. This impression is reinforced by the spacious, bright surfaces of the backrest upholstery on the interior in contrast to their dark, cohesive wood surfaces on the outside; here, a marquetry field has been set into the top third, clearly indicating that the back view of the chair is composed as its main visual feature.

This space is defined above not by the hitherto usual moulding but by a smooth, horizontal band of marquetry, which borders the tabletop and the backrests. Below, the marquetry band is again used for the optical cohesion of the group, placed at the same height on the legs of the table and chairs. The dining-room chair itself is fashioned solely out of two constructional elements: the rectangular panel of the backrest, reaching to the stretchers of the legs below, and the square pieces of wood in the same thickness as the backrest, which build the legs, seat frame and the Stretcher. The strong contrast already described above between the closed rear view of the chair and its open front view also corresponds to Moser’s choice of construction for legs, seat and stretchers. This allows a maximum potential in transparency, gained because his construction does not provide for a separate apron. The seat frame with its extremely flat upholstery is simultaneously the apron. It thus incorporates the thickness of the backrest, which shows the same flat upholstery. By setting the stretcher relatively high and its cross connection in the middle of the side stretcher, the latter is not visible from the front and hints merely at the contours of an elegant square, open below and in the same thickness as the seat and legs. The marquetry decoration likewise takes up the dominant constructional element of the square. The single decorative elements of the marquetry band are also squares with a disc in the middle of each. The marquetry field on the outside of the back is likewise inscribed in a square. It shows the front view of a dove with spread wings and an olive branch in its beak. We know from Berta Zuckerkandl’s report that Moser was alluding here to the new noble title “von Terramare” first awarded in 1901 to Isidor Eisler. At the same time she admired Moser’s “powerfully stylised solution” for this ornamental field and “broad, surface effect of the mother-of-pearl”, reminiscent of works by the japanese lacquer artist Ogata Korin. Moser must have seen this in 1900 at the japanese exhibition in the secession (vi secession exhibition). Despite the extraordinarily geometric abstraction of the chair, accentuating its basic constructional elements, Moser manages to bequeath it a prestigious character through the costly material and the elaborate craftsmanship. The result is a distinctively individual artistic product, typical of the modernism promoted by the secession.

CWD

Archive of the Dr. Hans and Gerta Eisler von Terramare’s apartment