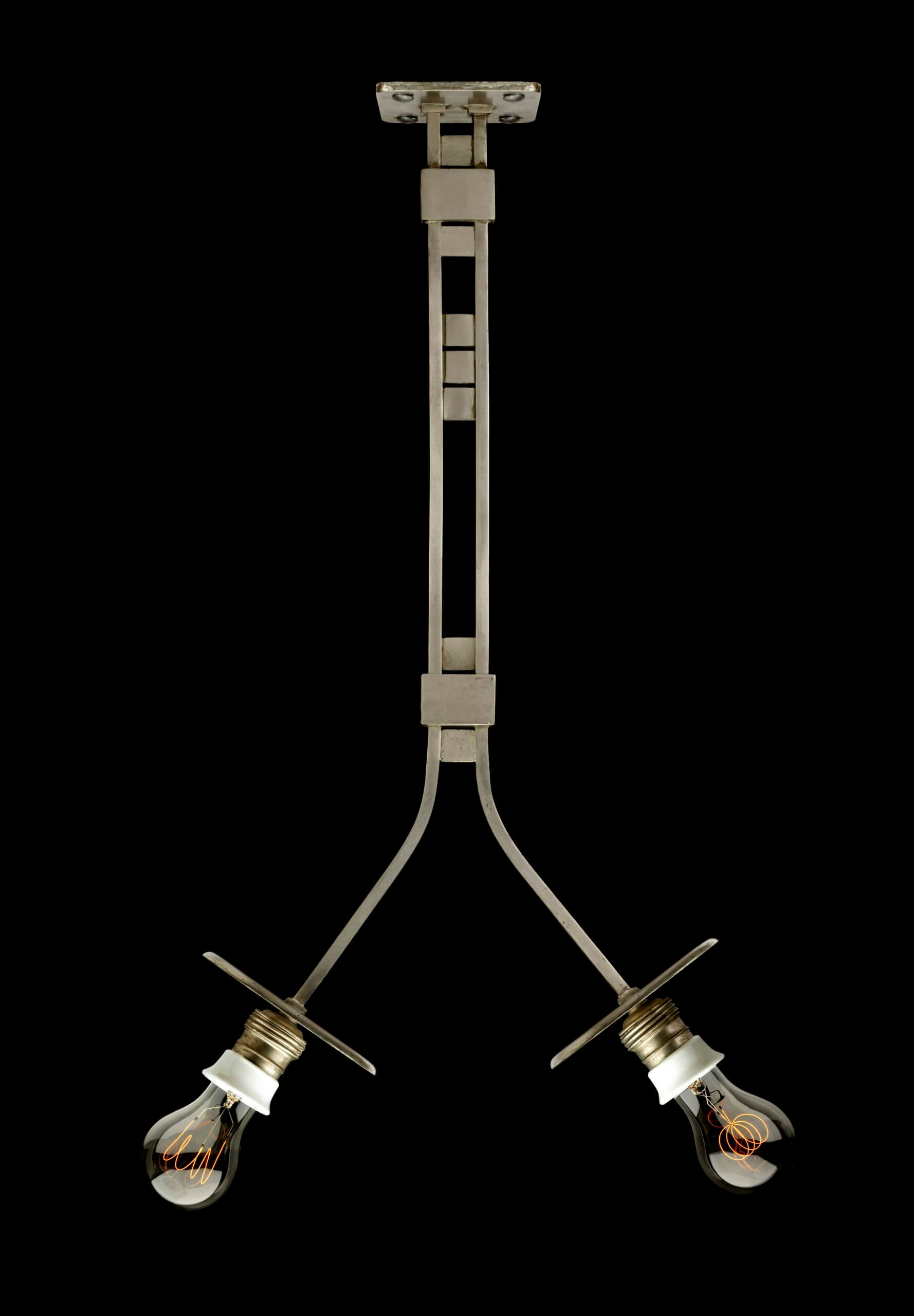

Made for

The dispatch bureau of “Die Zeit”

Year

1902

Material

Nickel-plated white metal, porcelain sockets

Dimensions

H. 60,3 x W. 33,5 cm

Similar piece

Neue Galerie, New-York

New Worlds – German and Austrian Art 1890-1940, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2001-2002

Vienna Art & Design, National Gallery Of Victoria, Melbourne, 2011

Ways To Modernism And Their Impact, Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, MAK, Vienna, 2014-2015

Otto Wagner, Wien Museum, Vienna, 2018

Asenbaum, P., Otto Wagner. Möbel Und Innenraüme, Salzburg & Vienna, Residenz Verlag, 1984, P. 198-201

Deutsche Kunst Und Dekoration, Vol.11, (December 1902), P. 117-120

New Worlds – German and Austrian Art 1890-1940, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2001, P. 418 (Ill.), P. 460 (Cat. Iii.5) (our lamp)

Vienna Art & Design, National Gallery Of Victoria, Melbourne, 2011, P. 56 (our lamp)

Otto Wagner, Wien Museum, Residenz Verlag, Wien, 2018, P. 372 (our lamp)

Sarnitz, A., Wagner, Germany, Taschen, 2005, P. 57

Chauveau. B., Otto Wagner Maitre de l’Art Nouveau Viennois, Bernard Chauveau édition, Wien Museum, 2018, P. 101

Something impractical cannot be beautiful.

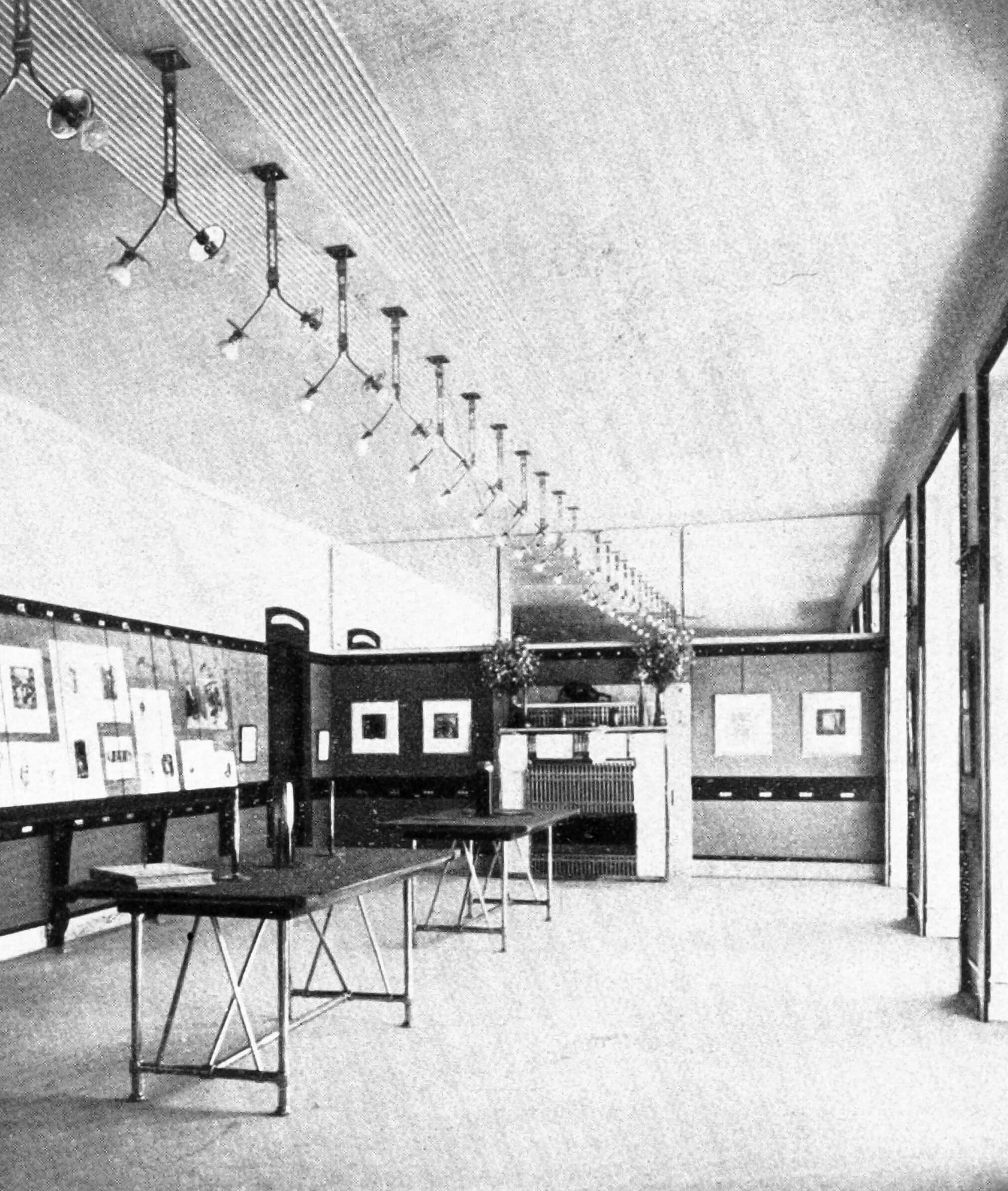

1902, Otto Wagner designed for the Viennese daily newspaper Die Zeit a street-level store, as well as a second-floor dispatch bureau on Kärntnerstrasse, one of the city’s most popular shopping street. In doing so, he formulated a completely new aesthetic for public space, based on the premise that “something impractical cannot be beautiful.” The selection and use of materials played a crucial role in the commission, spawning a material language that demanded of hte user a new kind of sensitivity, one irreconciliable with traditional ideas of ostentation.

As the most visible sign of his belief that new needs required new forms, Wagner designed the storefront out of aluminium, a material seldom used in Vienna at that time. For the interior he chose his materials based on durability, resistance to soiling, and ease of repair. The black/brown stained bentwood furniture and bentwood armchair stood out against a white wall protected up to roughly head level by grey-painted linoleum. For inlays and mounts on both furniture and plaster, aluminium which as Hevesi noted, does not oxidize was used. Similarly, the light fixtures for the dispatch bureau were not, as was common at the time, fashioned of brass, which involved complicated cleaning procedures, but of nickel-plated white metal. Together with the simple linear and geometric plasterwork, these formed the main decorative accent of the space. In between two broad, fluted plaster bands, the light fixtures, which each held two lightbulbs, were attached to the center of the ceiling in a single row down its length, one after another, visually not unlike track lighting. Their simple, stripped-down form, a radical break with traditional lighting fixtures of the pre-electric era, only revealed its full decorative and functional impact when viewed in the entirety of the space. The room’s artificial lighting was installed parallel to the three large windows that took up one of the room’s long sides. The intensity of the light was increased by mirrors attached to one of the room’s small sides, above the wall vitrines and thus above eye level. Here one is instantly reminded of the lighting solution used by Adolf Loos five years later in his American Bar. The ultimate effect is to transform the lights into a single huge fixture in the shape of a long band of light that defines the space.

CWD

Archive of the dispatch bureau of “Die Zeit”