Made for

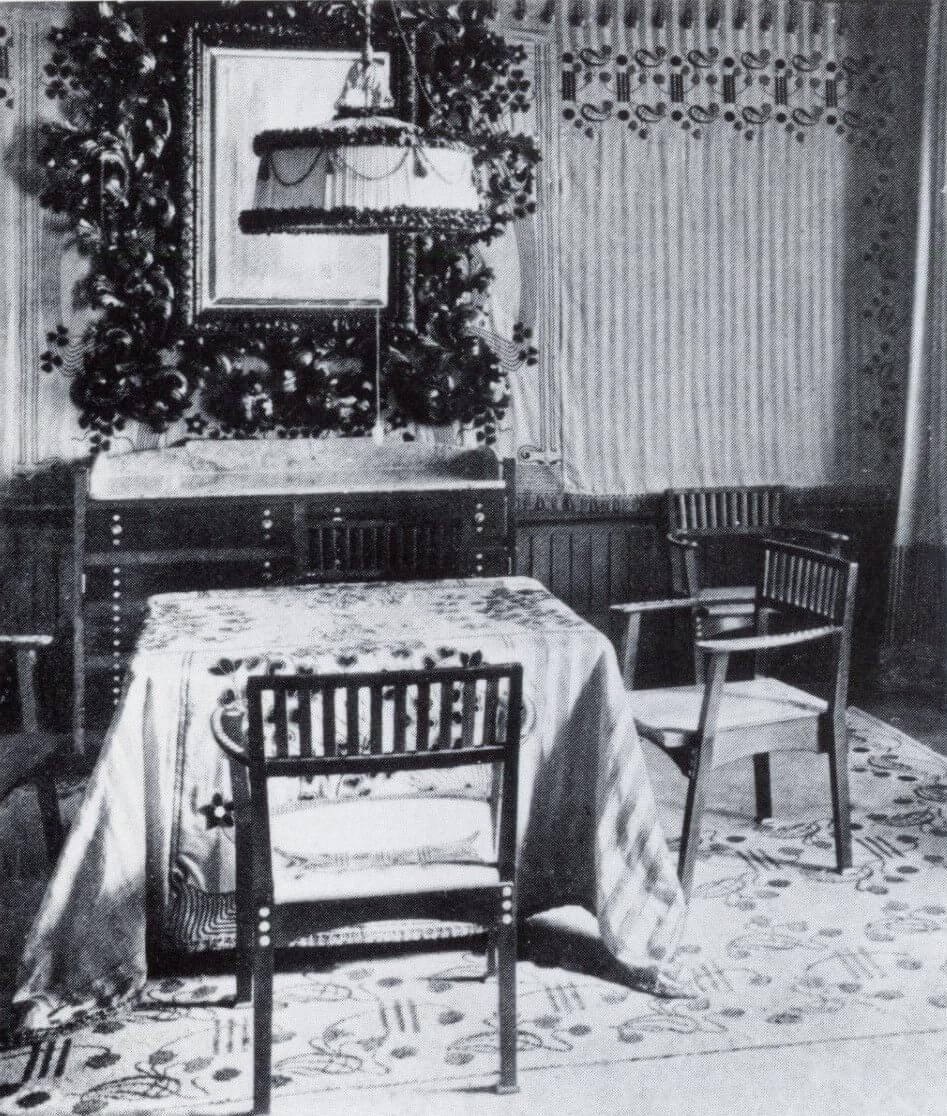

Otto Wagner’s dining room, Kostlergasse 3, Vienna

Year

C. 1898/99

Material

Wood, brass, mother of pearl

Dimensions

H. 84 x L. 69 x D. 60 cm

Similar Pieces

Victoria & Albert Museum, London (One small buffet & one armchair); The Art Institute Of Chicago (One armchair); Leopold Museum; MAK, Vienna (One large buffet)

WWMB-7-M-235

Wagner, O., Die Kunst Im Gewerbe, Ver Sacrum, III, Vienna 1900, P. 21, 295-298

Dekorative Kunst, Vol. VII, N° 4 (1901), P. 5

Asenbaum, P., Otto Wagner. Möbel Und Innenraüme, Salzburg & Wien, Residenz Verlag, 1984, P.36 N°36, P.80 N°87, P.103 N°129.

Asenbaum, P., Witt-Dörring, C., ‘Moderne Vergangenheit 1800-1900’, 1981, P. 28, 235-237.

Birth Of The Modern – Style And Identity In Vienna 1900, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2011, P. 92

Wagner, O., Die Baukunst Unserer Zeit; Vienna 1914, P. 18, 60

Jervis, S., Furniture Of About 1900 From Austria & Hungary In The Victoria & Albert Museum; London 1986, P. 68-69

Sarnitz, A., Wagner, Germany, Taschen, 2005, P. 52

Witt-Dörring, C., Otto Wagner Möbel, Gerstmayer, Vienna, 1991, P. 13

Every architectural form has arisen in construction and has successfully become an art form

The architect Otto Wagner may justifiably be called the father of Viennese Modernism. By 1890, he had already formulated his discomfort about the ruling artistic practice of his day of borrowing from historical styles for architecture and the design of everyday articles. In his opinion they no longer represented technological and social progress, nor the actual status quo of the time. For him, modern life was the only criterion on which to base artistic creativity in architecture. As alternative to outmoded historicism he conceived a practical style duty-bound purely to function, which, in addressing the individual stages in design, must logically lead to a modern solution.

As in a recipe, he set out the analytical procedure for this in his programmatic book “Moderne Baukunst” (Modern Architecture), which if applied honestly would automatically and unavoidably dictate the new language of forms:

I. Extremely precise grasp and complete fulfilment of the purpose (down to the smallest detail).

II. Felicitous choice of materials (i.e. easily attainable, readily adaptable, lasting, economical).

III. Simple and economic construction

IV. Only after consideration of these three main points, the form that evolves from these premises (which flows as though of its own volition from the pen and is always readily comprehensible).

For him, the beginning of a design process is not the artistic idea, but considerations that best comply with the purpose of the set task and its economic implementation. What mattered to Wagner was not the development of a formal, aesthetically defined modern style, such as was being propagated by the Vienna Secessionists, but a basic disposition faced with the needs and potential of modern everyday life. It is not the artist’s patronisation of the craftsman that leads to modern form, but knowledge about the material and constructional properties, and the appropriate practical use of such knowledge. Here Wagner takes first place as trailblazer of Modernism in the spirit of an Adolf Loos. “He is able to shed his ‘architect’s skin’ and slip at will into a ‘craftsman’s skin’”, Loos remarked in a rhapsodic discussion of Wagner’s bed and bathrooms shown at the Jubilee Exhibition in 1898.

The two rooms were part of a small pied-à-terre furnished by Wagner in the house he had designed and built on Köstlergasse 3 in the sixth Viennese district. His main residence at the time was in the Villa Wagner I, also of his own design, on Hüttelbergstrasse 26 on the outskirts of Vienna. The dining room – which contained the armchair discussed here – of the Köstlergasse apartment must have been furnished and ready by 1899, only a year after the exhibition. Wagner quickly published his interior design in the following year in Ver Sacrum, the magazine of the Vienna Secession. It is impossible to exaggerate the significance of this piece of seating furniture. It represents a completely new approach in Wagner’s oeuvre, standing out sharply from his previous seating furniture, until then strongly influenced by the Renaissance and Louis XVI styles. The significance attached by Wagner himself to this piece of furniture is manifest in his using it as initial vignette in 1900 for his article “Die Kunst im Gewerbe” (Art in Industry). Furthermore, he illustrated the armchair in the central chapter “Die Konstruktion” of the fourth (illustrated) edition of his book “Baukunst unserer Zeit” (Architecture of our Time) as a detail from the dining-room view with the programmatic caption “Construction, the origin of the art form” (Die Konstruktion, das Entstehen der Kunstform). Here Wagner refers to the text section highlighted in capital letters in the aforementioned chapter “Every architectural form has arisen in construction and has successfully become an art form.”

The armchair is indeed striking for its overall appearance assembled out of clearly defined horizontal and vertical constructional elements. There is no hint of them at any time diffusing into a flowing structural framework. The basic purpose of a piece of seating furniture of supporting and loading is unambiguously reflected in every single element. The extension of its four legs protruding outwards slightly at back and front configures the side boundary of the back rest and armrest supports. The apron is not constructed as a closed frame, but its single rails are fixed either to the inside of the legs or to the front and back sides of the legs, formally accentuating the construction. The leather seat covering a flat frame, originally adorned at front and back end with a tooled, partly floral and geometric pattern, juts out clearly with its rounded front edge over the front seat rail. Wagner meanwhile leaves the wood visible at the sides of the frame and extends the leather only over the rear and front side of the seat. This produces a clear differentiation between vertically supporting and horizontally loading constructional elements. Wagner doesn’t onset the armrests at a right angle to the backrest; in contrast to the square and oblong cross sections of the post construction, these are formed as flat, outwardly curving rails rounded at the front. Their join on the backrest is designed like a bracket, thus emphasising yet again the character of an autonomous constructional element. The interplay with the backrest, which likewise curves outwards slightly, creates a body-compliant “seating space”. The chair takes effect with hardly any reliance on decorative elements. But where they do come into play they have a quasi psychologically enlightening character. We can see this for example in the apron planks, cut out in an arch oriented towards the ground, a way of radiating tectonic and constructive stability for the seat; or the three mother-of-pearl discs arranged one above the other and attached to the ends of the front apron plank, which on the one hand symbolise fixedness and on the other emphasise the rail as an autonomous constructional element. In conclusion, Wagner adds a final finishing touch to the four legs by means of slightly protruding metal plates, planting the chair firmly on the ground and communicating constructional stability.

CWD

Archive pictures