Made for

17th Secession Exhibition, Vienna, 1903

Year

1902

Dimensions

H. 109,9 x W. 119,5 x D. 59,7 cm

Executed by

Portois & Fix

Material

Elm with rosewood, mother-of-pearl, ebony and ivory

17th Secession Exhibition, Vienna, 1903

Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture, Design, MoMA, New-York, 1986

Das Interieur, Vol. IV, 1903, P. 95

Hevesi. L., Acht Jahre Secession, Vienna, 1906, P. 431

The Silverman Collection, Richard Nagy Gallery, London, 2012, p. 160- 165

For the young generation of artists, the formal expressions of Biedermeier realized the first style not derived from an aristocratic lifestyle but suited to the needs of the bourgeoisie. It expressed itself primarily in a reduced, functional and modest idiom. Moreover, in Biedermeier culture the world of forms and everyday life had been in harmony for the last time prior to 1900. This defined an ideal that – contrary to Historicism, which was nurtured by a world of historical forms – was an essential precondition for life in the modern world of the middle classes. Unlike France, which endeavoured in the latter part of the nineteenth-century to rediscover its roots in the age of Louis XIV, a geometric- abstract idiom dominated visual language in Vienna.

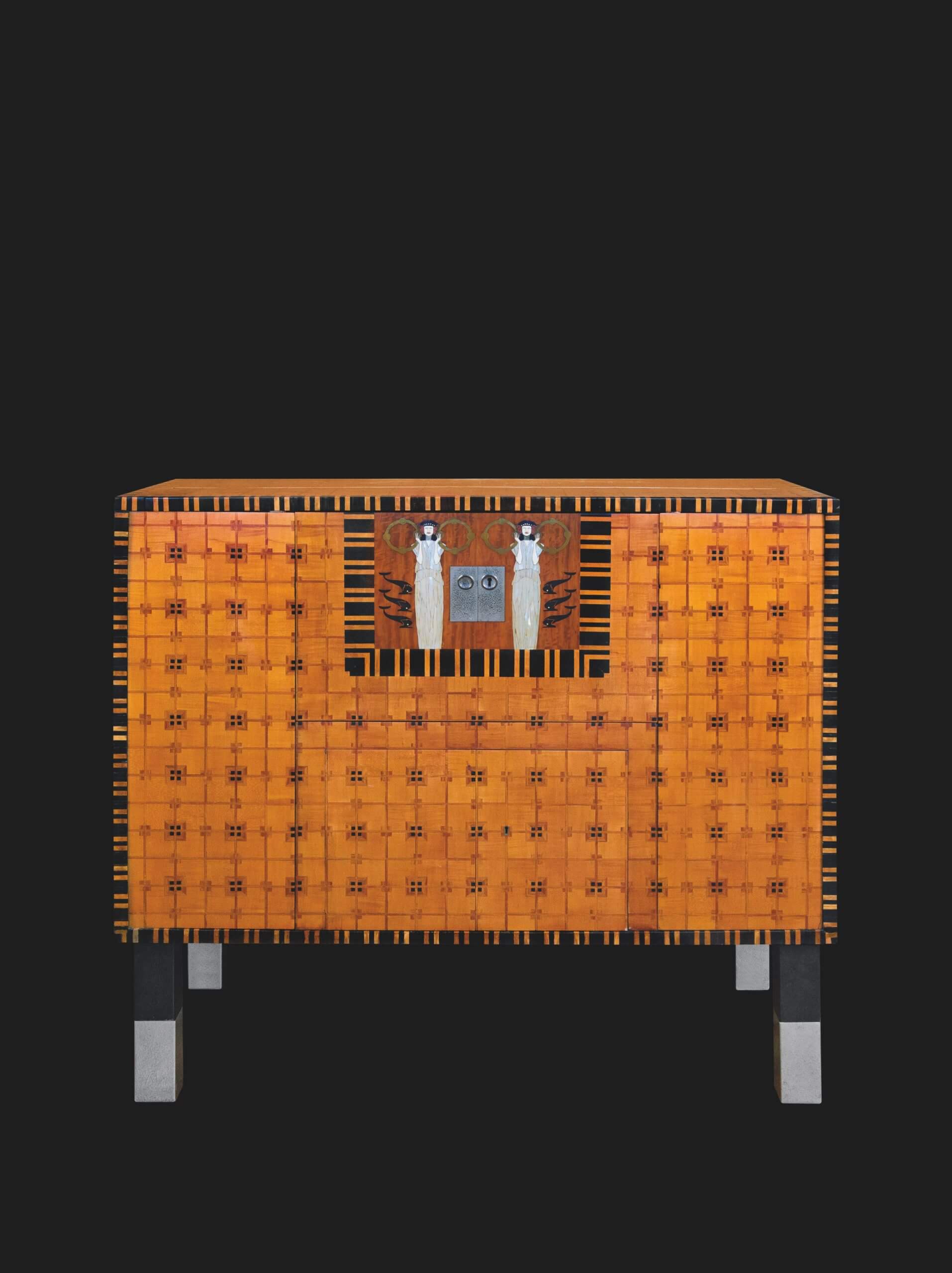

The writing cabinet presented here can be identified as one of two pieces of furniture designed by Moser in the Ver Sacrum room of the 17 th Secession Exhibition. In his review of the exhibition on 2 April 1903, the art critic Ludwig Hevesi writes: ‘In this room we see two remarkable, light cabinets by Moser, in the simplest cubic forms, but appetizing (“appetitlich”) in material and foldable like Old Japan.’ Conclusive proof that he was writing about this very piece is provided by the exhibition catalogue, which mentions a writing cabinet in the Ver Sacrum room. Since the exhibition had already opened on 26 March 1903, Moser must have completed the design for the elaborate execution by the end of 1902. Hevesi’s description of the writing cabinet might be difficult to comprehend in terms of today. The attribute ‘appetitlich’ (appetizing) as an adjective for a piece of furniture is surprising, but understandable in the context of Hevesi’s emphasis on the bright finishing. In contrast to the then current fashion in Historicism,which favoured sombre surroundings and shutting out daylight – thus keeping the public eye out of the private sphere of the home, the Secessionists propagated a bright atmosphere connecting the inside and the outside world. Light surfaces were felt to be hygienic and therefore appetizing, or pleasing. Hevesi’s association of the piece with Japan does indeed refer to its function as a writing desk, only visible when unfolding horizontal and vertical elements, but may be extended to include the Japanese woodcuts and dyers’ stencils that were such important sources of inspiration for Moser’s planar art.

The writing cabinet betrays the painter, who doesn’t think a priori in tectonic dimensions.

For him, this cuboid-shaped carcass furniture is not constructed of bearing and loading elements, but consists of individual planes that might be interpreted as support for images.

The front and side walls of the writing cabinet are covered with geometric marquetry and framed dark, awakening the impression that the piece is constructed of single planes. Moser consequently sets the legs directly onto the front and rear walls, without the intermediary element of a horizontal bearing element like an apron. This gives the effect of a retractable telescope, which keeps the cabinet in a visually precarious state. The same artistic approach defines Moser’s design for the Klimt Collective in 1903 as part of the 18th Secession Exhibition. He frames the bright gallery walls with greyish-gold geometric ornamental bars, thus creating an effect of ephemerality in the material space. In contrast to the architect Josef Hoffmann, who employs framing elements in his furniture designs and interiors in order to define and generate space, Moser uses them to accentuate the individual planes.

Moser’s writing cabinet is first and foremost an art object – its function is not immediately accessible. As in an item of Biedermeier furniture, where the veneer is applied to create the visual impression of a uniform and uninterrupted surface across horizontal and vertical structural elements, Moser subordinates the function to the retention of an intact surface decoration. The symmetrically arranged escutcheons hint at a sideways opening at centre front; whereas half of the top folds upwards, the two outside quarters of the front open to the left and right. Only after this is done can the actual desk board with the figural decoration on the front be dropped down. This decorative element harmonizing with the proportions of the front not only recalls the monumental locks on sixteenth-century Spanish vargeñ uos, but is also similarly placed, namely in the top centre of the front. Conversant with the artistic and handcrafted achievements of earlier generations, Moser manages to reinterpret traditional contents and discover his own independent, modern idiom.

CWD

Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture, Design, MoMA, New-York, 1986