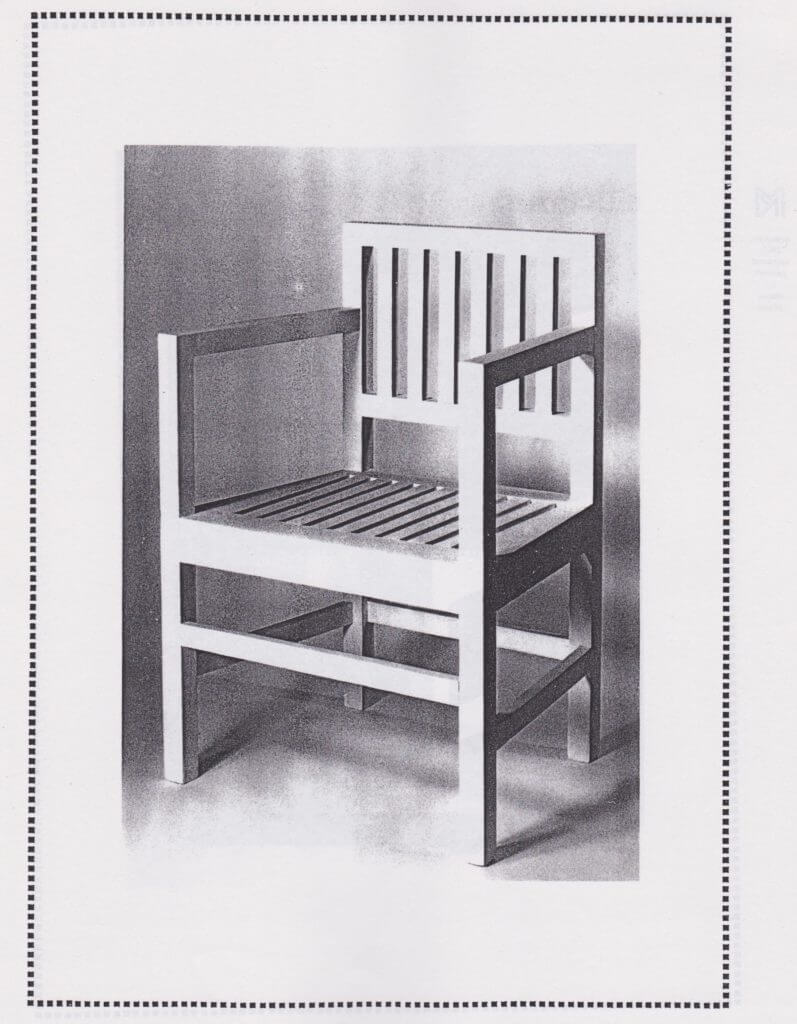

Made for

The Moser’s House in the Hohe Warte quarter, Vienna

Year

1901

Material

Pine wood painted

Dimensions

H. 89,5 x L. 60 x P. 50 cm

Unique Pieces

Yearning for the Beauty, The Wiener Werkstätte and The Stoclet House, MAK/Bozar, Brussels, 2006

Koloman Moser 1868-1918, Leopold Museum, Vienna, 2007

Koloman Moser: Designing Modern Vienna 1897-1907, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2013

Koloman Moser Universal Artist between Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann, MAK, Vienna, 2018-2019

Yearning For The Beauty, The Wiener Werkstätte And The Stoclet House, MAK/Bozar, Brussels, 2006, P. 27, Ref. S8

Koloman Moser 1868-1918, Rudolf Leopold, Museum Leopold, Prestel Editions, 2007, P. 157

Koloman Moser, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2013, P. 314

Koloman Moser (1868-1918) alongside Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich was one of the most visionary founding members of the Vienna Secession. Established in 1897 with the objective of helping the modern movement – already fully developed in Western Europe – to a breakthrough in Austria as well, the Secession postulated the development of an independent, modern, Austrian and civil style. They oriented themselves towards the English Arts & Crafts movement, which supported the equality and unity of the arts (as arts and crafts) and a return to quality handicraft. The artist thus took over responsibility for the formation of everyday life, which owing to the negative effects of industrial production had already reached a cultural nadir in both moral and aesthetic terms in England by 1860. This aimed to guarantee that with artistic design as intermediary, beauty would find a way back into life and make it more worth living. In Vienna this ideology, inspired by England and mediated through Van de Velde and the Munich Secession, led to the realisation of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total, synaesthetic work of art, as a habitat designed throughout in artistic unity. In the final consequence, this become uncompromising reality in the Wiener Werkstätte, an artists’ and craftsman’s cooperative founded by Moser, Hoffmann and the financier Fritz Wärndorfer in 1903.

Moser was actually trained as a painter at the Vienna Academy of Arts from 1886 to 1892; by 1897 in the context of the Secessionists he had begun to engage in the designs of everyday objects. At the start he concentrated exclusively on the development of a modern ornamental idiom, which found its practical expression in artistic fabric and carpet designs for the Backhausen Company. These works inherently belonged to the two-dimensional medium of the canvas; then in 1899, caught up with the idea of the unity of the arts, he discovered the three-dimensional potential of the media of clay and glass, which he implemented in a number of vases and drinking glass designs. This artistic versatility led the art and culture critic Hermann Bahr to characterise Moser as a jack of all trades. While these first handcrafted works were still strongly influenced by international, curvilinear Art Nouveau, since 1900 a special Austrian language of forms was beginning to assert itself in accordance with the Secessionist aim. It was born of the wilful return to national roots found in the Neo-classical formal vocabulary of Biedermeier. Its main characteristic involves an aesthetic based on symmetry, frontal focus and geometrical, abstract forms.

The year 1900 thus marked a momentous artistic turning point in both Moser’s and Hoffmann’s oeuvre, which resulted in Vienna’s independent and internationally unique path into Modernism. The two armchairs presented here are prime examples of this achievement. Moser designed them for the veranda of his own house in Vienna-Heiligenstadt, designed by Hoffmann in 1900/01. It was the first of a series of buildings planned by Hoffmann between 1900 and 1909 for the villa colony on Hohe Warte, whose owners had a close affinity to the artistic ideas of the Secession. Moser resided in the building –planned as a double house for himself and Carl Moll, the painter and founding member of the Secession – with his mother and his sister until his marriage to Ditha Mautner von Markhof in 1905. Reduced to its constructional elements this chair unfolds a subtly elegant aesthetic based on Moser’s design practice of developing forms out the flatness of the painter’s medium, the canvas, into the three-dimensionality of the world of objects. In contrast to the work of his fellow artist, the architect Josef Hoffmann, the result is a fascinating ambiguity between space and flatness, which makes tectonic considerations recede into the background.

The year 1900 thus marked a momentous artistic turning point in both Moser’s and Hoffmann’s oeuvre, which resulted in Vienna’s independent and internationally unique path into Modernism. The two armchairs presented here are prime examples of this achievement.

Basically structured out of right-angled constructional elements and connections, the armchair nevertheless has a trapezoidal seat. This actuates a scarcely definable but palpable movement in the rigid construction of the framework. Moser doesn’t set the front stretcher at the same height as the others but a little higher, hence this element of movement finds a subtle correspondence here. He arranges all constructional elements together flush on the outer sides of the chair. This is especially notable in the stretchers, dimensioned somewhat smaller than the legs and the vertical slats of the backrest. Moser thus simultaneously accentuates the flatness of his four fronts in contrast to the three-dimensional but permeable volume of the chair. This initially irritating but thoroughly consistent approach is reinforced through the apron boards, much thicker than all other constructional elements. In this way Moser succeeds in engaging the observer and thus the user in a discourse with the chair. The viewer is compelled to come to terms with the object, to make it his own. In these terms it is a modern product that also lets the individual have his say. Visual habits that are unaccustomed and able to provoke visual insecurities can thus lead to a new and suspenseful visual experience.

« A private photo of Moser’s house, which has remained in the possession of the family, shows Moser’s wife Ditha and his mother on the veranda on the garden side of the house. It documents that Kolo Moser used objects he had designed in his everyday life : on the table can be seen the square ashtray which was one of Moser’s first metal objects for the Wiener Werkstätte ; the half-empty wine glass (which can be partly seen in the picture on the right-hand side) is part of Moser’s Diner Service No.100 Meteor for E. Bakalowits Söhne. The armchair which can be seen on the veranda, which has been positioned as a show item, provides a good impression of the items of furniture which Kolo Moser designed for the house, as do the chest of drawers and the wall unit from the study on the lower ground floor. Their simple clarity, determined by the stereometric forms, and the conscious simplicity of material and the white lacquer surface framed with blue or black, down to the massive beaten metal handles, demonstrate Moser’s idea of functional furniture, which derives its beauty from its practicality in conjunction with proportion and the finish of the materials.

Following his marriage to Ditha Mautner von Markhof, Kolo Moser moved in 1905 to an apartment in the garden wing of the Mautner villa at Landstrasser Hauptstrasse 138, which he had had furnished by the Wiener Werkstätte in accordance with his own designs. From July 23, 1905, Kolo Moser was officially registered as resident there. The house on the Hohe Warte remained in the possession of the family. Moser’s mother continued to live there until her death in 1926. The Moser house on the Hohe Warte still stands today but has undergone a number of changes which nonetheless still permit the original overall appearance to be recognized. The interior of the house has been changed considerably by a succession of subsequent owners.»

CWD