Made for

The Stonborough-Wittgenstein apartment in Berlin

Year

1905

Material

Original white lacquered wood

Dimensions

H. 184 x L. 59,5 x D. 48,5 cm

Executed by

The Wiener Werkstätte

2 Pieces Made

Similar Pieces

MAK, Vienna; Louvre, Abu Dhabi

Deutsche Kunst Und Dekoration, 1906, Vol. XVII, P. 149,163

Witt-Döring, C., Josef Hoffmann – Interiors 1902-1913, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2006, P. 186, 209

Louvre Abu Dhabi – Naissance D’un Musee, Louvre, Paris, 2013, P. 273

The design of the cupboards manifests the aesthetic approach typical of Moser, based on the fact that Moser was trained as a painter and not as an architect

On the marriage of his daughter Margaret (* 1882 Neuwaldegg near Vienna) with Dr. phil. Jerome Stonborough (* 1873 New York) and their prospective removal to Berlin, Karl Wittgenstein commissioned Hoffmann and Moser to design their future apartment in the city, and the Wiener Werkstätte to execute the designs. The rented property was situated in one of the best Berlin residential areas on Zelten 21a near the Tiergarten. The house itself was designed in 1887/88 in Renaissance style by the Berlin architect Paul Ferdinand. The apartment consisted of six rooms (Herrenzimmer – a combination of study and smoking-room, Damenzimmer – parlour; dining room, bedroom, dressing room and nursery), a vestibule with connected hallway, a servant’s room, a kitchen, a pantry and a bathroom. The furnishing presented here comes from the dressing room.

The apartment must have been ready to move into by April 1905, since Margaret wrote to her mother in Vienna on 18 April: “Moser – who was again utterly charming – and I have been moving furniture around for three whole days, hanging up pictures and painting frames. Now the flat is in order, at least outwardly, and Jerome and I are delighted and sing your praises and those of the Wiener Werkstätte every day.” To complete the household, Margaret Stonborough bought a number of silver utensils at the Wiener Werkstätte exhibition of autumn 1904 in the Hohenzollern Kunstgewerbehaus in Berlin. The apartment existed only until and including 1907, for no corresponding entry can be found after this year in the Berlin municipal address register. During this period her son Thomas was born in Berlin on 6 January 1906.

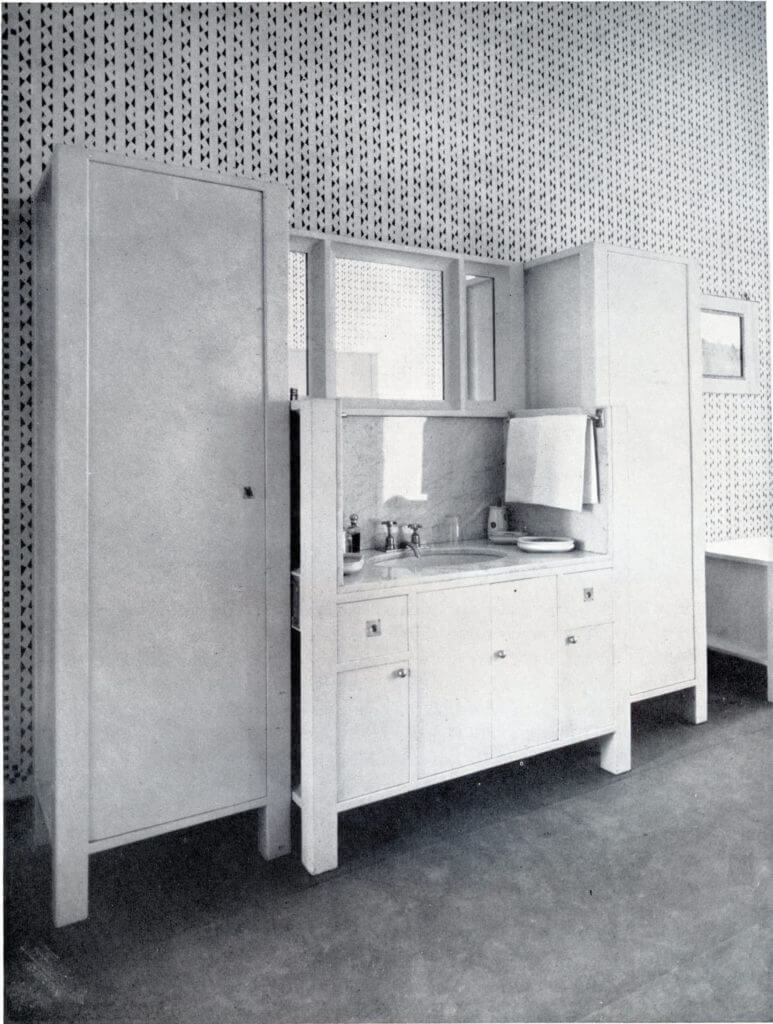

The single-door cupboard and the two double-door cupboards come from the apartment dressing room designed by Koloman Moser. The single- door cupboard was likewise flanked with the washstand while the two double-door cupboards were originally placed separated by a narrow mirror of the same height on the longer wall of the dressing room.

The same model but with silver relief inlays was also placed in the bedroom of Jerome and Margaret Stonborough and in the patient rooms of the Purkersdorf Sanatorium. In the latter, Moser designed the cupboards on ball feet with integrated castors.

The design of the cupboards manifests the aesthetic approach typical of Moser, based on the fact that Moser was trained as a painter and not as an architect. His treatment of tectonics is much freer than is evident in Hoffmann’s furniture designs. The cupboard doors seem to be clamped between two posts. They find no counter bearing whatever in them. The different dimensioning of the broad, vertical posts and of the much narrower horizontal frieze banishes any thought of frame construction. Since the vertical posts run through uninterrupted from bottom to top, there are no optical hints whatever of a base that could support the cupboard. Nor is there a clear horizontal finish towards the top that could assume the tectonic role of a cornice. The cupboard doors appear as if they are able to slide to and from between the posts. Seen from the front, the cupboard has no depth at all. It consists solely of planar surface. On the side walls, Moser turns planarity into its exact opposite and creates space through a kind of chamfering. The different dimensioning of the vertical and horizontal framing elements is maintained here, as at the front, which means that the frame cannot act as a tectonic element here either. It takes effect at top and bottom more like a stuck-on decorative element, which could be extended at will in both directions. All in all, the cupboards testify unambiguously to one of the major characteristic features of Viennese design practice around 1906 – ambiguity. It is directly related to the search for individual aesthetic expression, which also encourages the active role of the viewer. Ambiguity opens up possibilities of interpretation and thus participation.

CWD