Made for

The apartment of Dr. Hugo Koller and his wife Broncia Koller-Pinell

Year

1904

Material

Limed oak solid and veneered, stained black, sycamore veneer, white metal

Dimensions

H. 78,5 x W. 69,5 x D. 69,5 cm

3 Pieces Known, Similar Piece

Wiener Werkstätte, 1903 – 1932 : The Luxury Of Beauty, Neue Galerie, New-York 2017

Decorative Arts 1900 – Highlights From Private Collections In Detroit, Detroit, The Detroit Institute Of Arts, 1994, P. 75.

Sekler, E., L’oeuvre Architecturale de Josef Hoffmann, Salzburg-Wien, 1982, Cat. No 98.

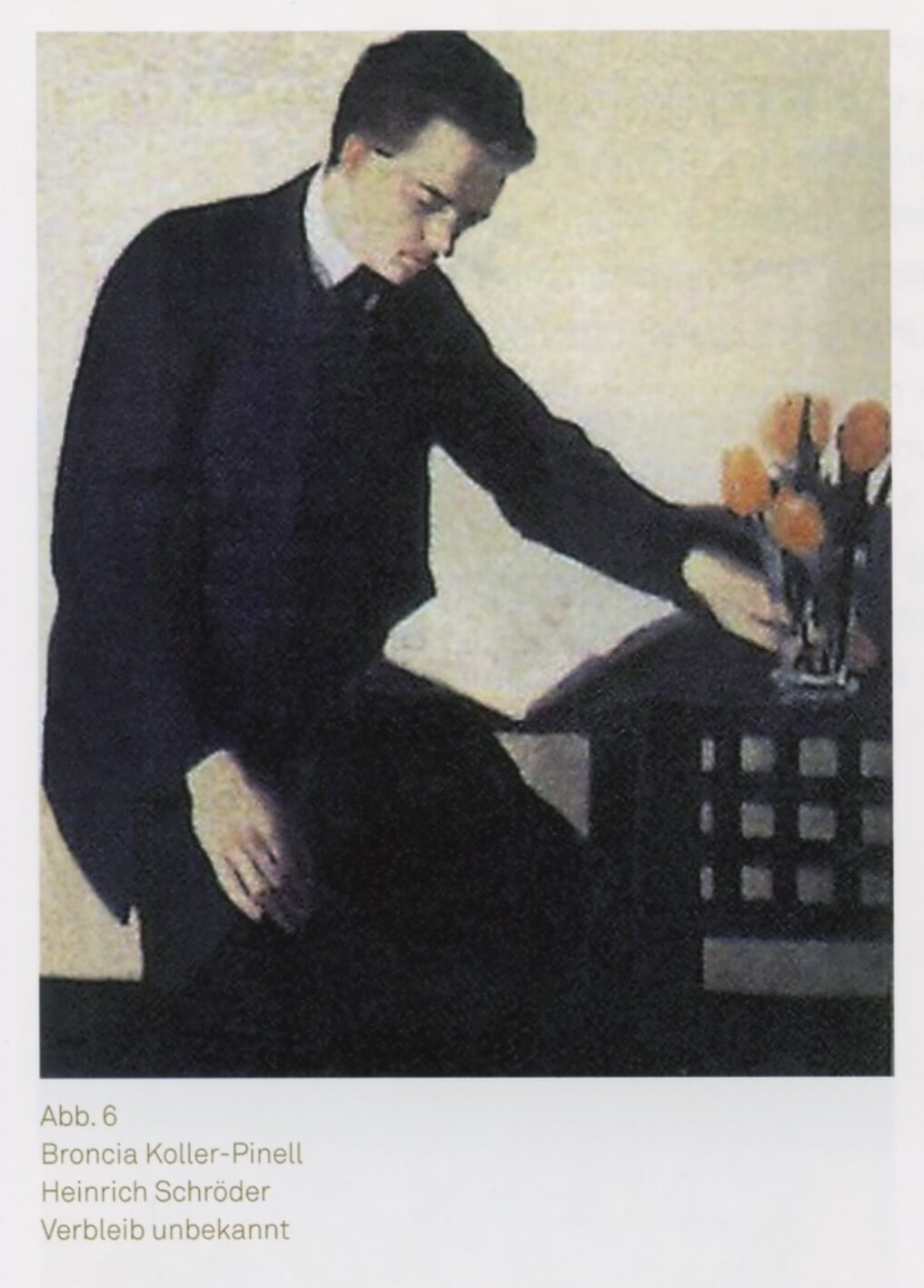

Tobias Natter (Ed.), Broncia Koller-Pinell. Eine Malerin Im Glanz Der Wiener Jahrhundertwende, Jüdisches Museum Der Stadt Wien, Vienna, 1993

Gustav Klimt Und Die Kunstschau 1908, Belvedere, Vienna, 2008-2009, P. 164

Deutsche Kunst Und Dekoration, Vol. XVI., 1905, P. 563

Deutsche Kunst Und Dekoration, XVII, 1905, P. 149f

Wiener Werkstätte Archive: WWF 101, P. 28

Aesthetic idiom that is reduced to a minimum

This table is one of three preserved examples. The other two are today in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and in a private collection in Detroit. It is documented three times in contemporary photographs from 1904, 1905 and 1912. The earliest photo shows it in 1904 as part of Hoffmann’s interior design already executed in 1901/02 for the apartment of the physician and physics scientist Dr Hugo Koller and his wife, the painter Broncia Koller-Pinell, in Vienna 4; Argentinierstrasse 26 (formerly Alleegasse). It stands in an alcove lined with a three-sided bench in the study fitted out for Dr Koller by Koloman Moser in 1904. It crops up again in a photo taken of the music room in 1912, planned by Josef Hoffmann as part of the redesign of the Koller apartment. The 1905 photo shows it in the centre of the large exhibition room of the Galerie Miethke as part of a presentation of works from the very recently founded Wiener Werkstätte.

The table designed by Josef Hoffmann in 1904 is one of the earliest pieces of Wiener Werkstätte furniture. It manifests Hoffmann’s then typical language of forms and already features his mature style dominated by geometric forms. Looking at it superficially, we are confronted with an aesthetic idiom that is reduced to a minimum, leaving the impression of a table bereft of everything except its most essential constructional and functional elements. This would mean that the sum total of its role is performed purely through the basic bearing and loading functions of four legs and a top. But this would be an extremely one-sided and entirely uncomprehending and un- derestimating view of the table’s true character. Hoffmann’s quality and great creative achievement only becomes manifest through a meditative approach, which this table so to speak invites and enables. Nothing about this table is standard. Hoffmann’s aesthetic vocabulary has an almost banal familiarity about it, but he forges it into an idiom that is unfamiliar to us and crosses the threshold to a new culture.

Hoffmann couldn’t have found a clearer expression of the bearing and loading functions than in the contrast between heavy legs and buoyant top – the table almost seems earthed through the slight downward flare of the legs. Yet the impression lingers of an unsteady assembly. The conspicuously protruding top, thin in contrast to the sturdiness of the legs, is placed directly onto the legs. It appears to float and seems easily removable. Its black materiality is moreover visually mitigated by means of bright sycamore squares at the corners, which jut out into the surrounding space. Hence it seems to have no defined contours determining a beginning and an end. Hoffmann opposes the vertical bearing structure of the legs with a comparatively weak, horizontal loading di- rection. He generates the visual and tectonically reassuring tension between these two elements – normally enacted by an apron – as square latticework. But the table doesn’t have an actual apron. It is interpreted transparently. Nor does the tension between the two opposing forces of bearing and loading materialize in the form of a foot cross. Hoffmann actually heightens the tension by making the legs seem long in relation to the table top, an impression intensified yet again by a non-existent solid apron, respectively its merely visual fitting between the legs in the form of the lattice work with- out a super-ordinate frame. In the end, Hoffmann does after all give a horizontal orientation to the table at floor level by adding the thin, nickel plated metal mounts. Their low level is proof that this is an aesthetic intervention to compensate for the dominant horizontal line of the table top, and not a functional protection against wear and tear as is familiar in rococo furniture.

CWD

Archive pictures

Wiener Werkstätte, 1903 – 1932 : The Luxury Of Beauty, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2017