Year

1912

Material

Silver and malachite

Dimensions

H. 18 cm x H. 19 cm

Executed by

The Wiener Werkstätte

Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932, Panasonic Shiodome Museum, Tokyo, 2011

Waltraud Neuwirth; Josef Hoffmann – Bestecke Für Die Wiener-Werkstätte: Inv. Cat. Of The Austrian Museum Of Applied Arts, Vienna 1982, P. 212

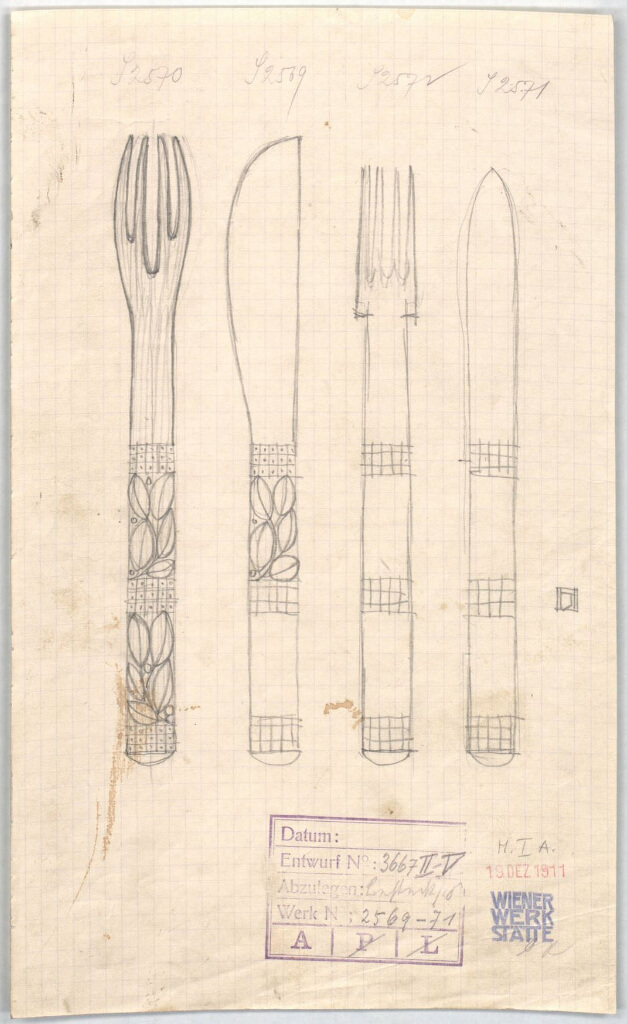

Archive of The Wiener Werkstätte; WWE 4/1, WWMB 15, P. 2569-72, WWF 95, P. 157 (Fish-Serving Cutlery)

Around 1900, for the first time in the history of mankind, the decorative arts were given a social and economic-political role of hitherto unprecedented importance. Born of the conviction that the modern, twentieth-century human being needed an appropriately modern language of forms to support his and her individual requirements, the western art scene committed itself to its aesthetic and technical realisation.

The architect, as the representative of an art discipline mediating between function and creativity, saw himself around 1900 as the guarantor for this visual reform of people’s everyday lives. Loos, however, saw the reform endangered by a purely superficial aesthetic approach and fought for his principal idea of a cultural re-proselytisation, which would make Austria a part of western culture once more. He assigned this role in 1898 to the profession of the architect: “He doesn’t have to know the cultural needs of his time precisely, but he has to stand at the vanguard of this culture.” His rejection of Hoffmann-type creativity has to be understood with this in mind: “In order to find the style of our time, we have to be modern people. But people who seek to change the things that are already in the style of our time or wish to replace them with other forms – I’m only referring to cutlery – show that they don’t recognise the style of our time. They will seek it in vain.” And further: “For me, tradition is everything; giving a free rein to the imagination only comes second for me.” The definition of this idea of tradition to which Hoffmann – just like Loos – committed himself on founding the Wiener Werkstätte clarifies the difference between the two positions. While Loos propagated the traditional separation of art and handicraft as one of his key statements, Hoffmann saw the link-up with a lost standard of quality guaranteed in the revival of the handicraft tradition, led by the artist or architect.

No example within the decorative arts is better qualified to illustrate these ideas on the theory of design than the cutlery designed by Hoffmann in 1912 and executed by the Wiener Werkstätte. It was made during the time of the first, major economic problems for the Wiener Werkstätte and strikingly manifests the inadequacies of fin-de-siècle Viennese aestheticism in terms of realpolitik. The reform movement surrounding the young Josef Hoffmann was initially oriented on idealistic, democratically motivated ideas, but very soon backlashed into a movement motivated by artistic self-fulfilment. This meant concentration on the production of luxury goods of the highest artistic and handcrafted quality, and the exclusive concentration and reliance on wealthy patrons – a situation that deprived the Wiener Werkstätte firstly of the broad-based effect of social reform it initially aspired to and secondly the required realistic base for the economic enactment of its concept.

The extremely luxurious execution of this silvery cutlery with malachite cabochons seems to be one reason that the Wiener Werkstätte produced only fish knife and fork, fruit knife and fork, and a fish–serving set of knife and fork from this cutlery model (S 2569-74). Certainly conceived originally as a complete cutlery service, in January 1912 the Wiener Werkstätte produced no more than 24 fish knives and forks at a selling price of 20 crowns each, then in February 1912 24 fruit knives and forks at a selling price of 18.50 crowns each, and finally the fish servers. No specifications on a purchaser appear in the Wiener Werkstätte order books, so it seems plausible that Hoffmann primarily planned the realisation of a new design idea and thoughts of selling were only secondary. In design, this model is an extremely more luxurious version of his “round model” of 1907 conceived for the furnishings of the Cabaret Fledermaus. Instead of the plain, smooth surface of the handles there is a grid pattern in relief interrupted by laurel sprays, and in place of the smooth, domed end of the handle a malachite cabochon is fitted.

CWD