Made for

Baroness Magda Mautner von Markhof‘s apartment

Year

1903

Material

Nickel plated brass and bevelled glass

Dimensions

H. 140 x Diam. 30 cm

2 Pieces Made, One Known

Innen Dekoration, XVI, 1905, P. 189

Sekler, E. F., L’œuvre Architectural de Josef Hoffmann, Pierre Mardaga, Bruxelles, 1986, Co 68, P. 277

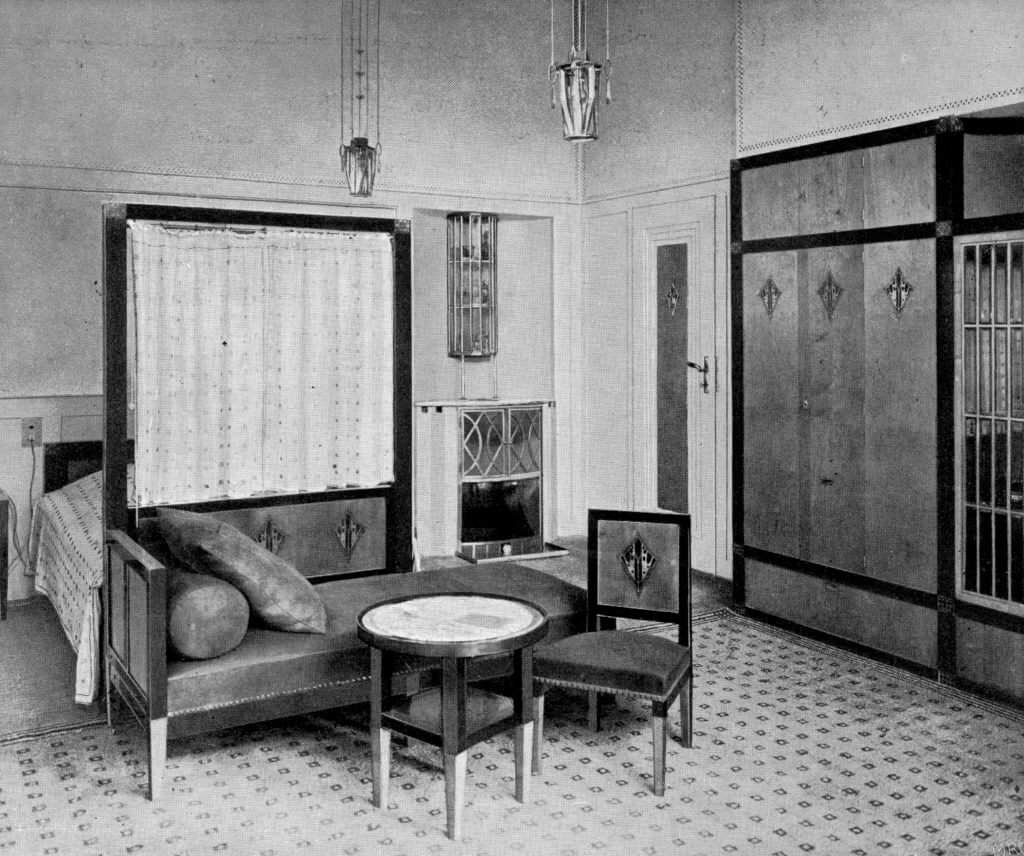

In 1902 Baroness Magda Mautner von Markhof, the wife of the beer manufacturer and yeast producer Carl Ferdinand Mautner von Markhof, started the refurbishment of her house on Landstrasse-Hauptstrasse 138 in Vienna’s third district with the redesign of a living room and bedroom. She entrusted this task to Josef Hoffmann, the head of the architecture class at the Vienna School of Decorative Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule). It was no coincidence that she opted for a representative of the Vienna Secession as interior designer of her house. Her daughter Editha was enrolled at the School of Decorative Arts as a pupil of the two founding members of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser. This first commission from the Mautner family was the start of a number of other interior design assignments, including for Magda, Editha’s sister. The latter eventually married Koloman Moser in 1905; he converted to the Protestant faith to do so, thus losing the commission to design the high altar of the Catholic church at Steinhof.

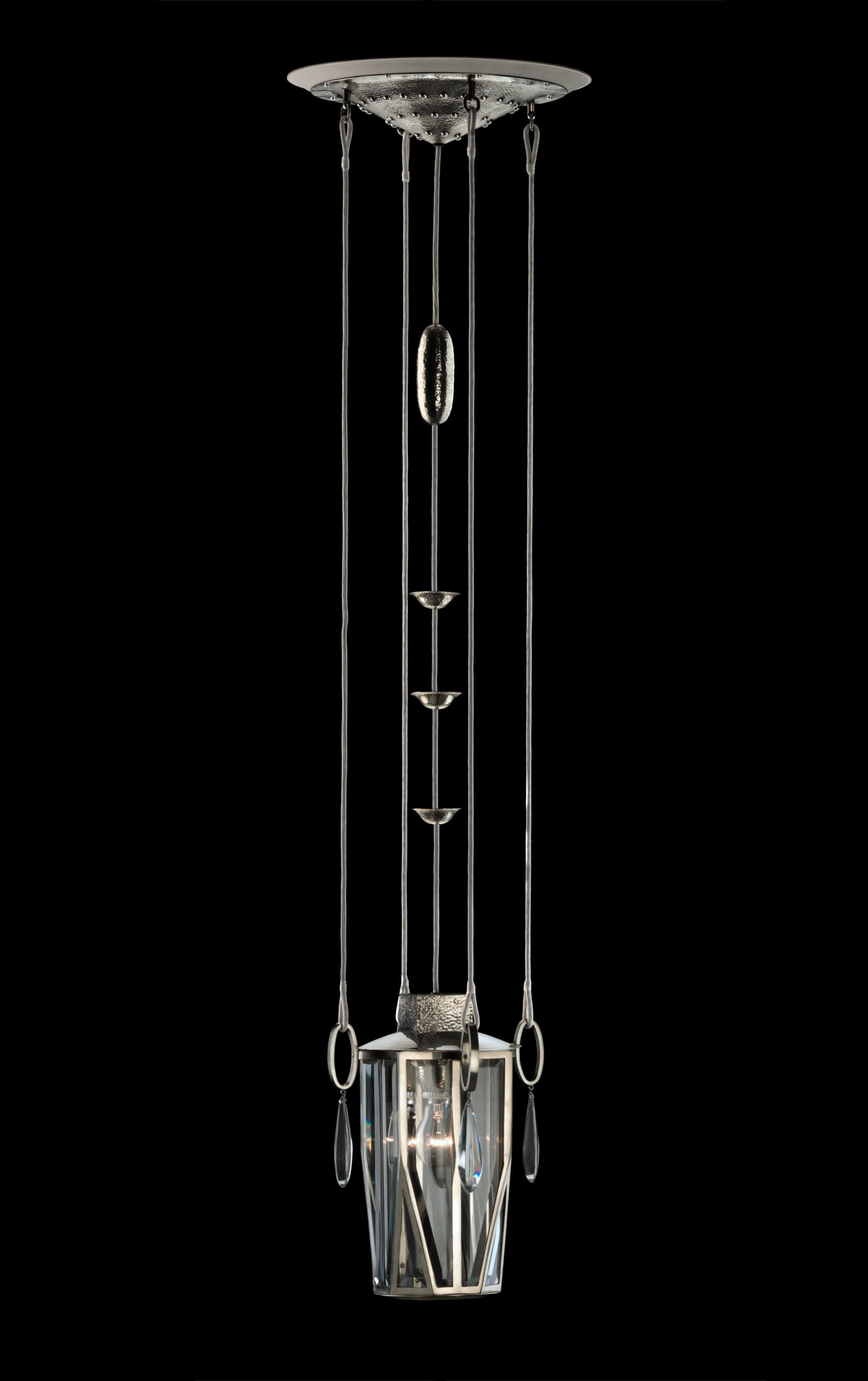

This lamp was part of a lighting system probably consisting of two single pieces and attached in the middle of the ceiling aligned to the axis of the bed in Magda Mautner von Markhof’s bedroom. Typologically it belongs to the pendant lamps that were extremely popular from 1900 on, which were beginning to exploit to its full artistic potential the advantages of the enclosed electric light instead of naked gas- or candlelight. Aesthetically it is a unique piece in Hoffmann’s oeuvre, which re-interprets two traditional elements – the lantern and pendant chandelier decorations – into a new unity. The lamps have to be appreciated as an integral part of the total spatial experience conceived by Hoffmann. They form a clear, spatial counterweight to the other furnishings in the room, which are structured as a unity through a uniform height horizon. They enable Hoffmann to connect the upper third of the room – deliberately left empty – with the furnished lower part. The lamp’s design thus engages his main attention in addressing this task. He reaches the solution by skilfully exploiting horizontal and vertical elements, which then reflect the main structural details of the room and thus unite the pendant lamps with the ambience into an integral design.

The primary impression made by the lamp is vertical. It is defined by the five cables on which the lantern corpus is suspended, with the middle cable providing the electricity supply. It becomes the central supporting element through the decorative metal elements threaded onto it. Three of these elements are designed as bulbous discs, functioning like an arrowed line as a psychological moment of expectation for the actual light source, the electric bulb. Further vertical elements are formed by the four emphatically oblong oval rings, the fixtures for the four outer cables. These supports are not integrated unobtrusively as a necessary evil into the top cover plate of the lantern body – as we might traditionally expect – but conspicuously protrude as a visible, self-assured design detail. This ensures that their vertical effect is shown fully to advantage; furthermore, they are able to support oblong, cut-glass elements on their bottom end, borrowing from the traditional repertoire of pendant chandelier decorations. In obedience to the vertical tendency of the total concept, the lantern corpus is not only formed longitudinally, but is enhanced by the sophisticated trick of tapering downwards. Starting out from a larger, square top-end of the lantern, Hoffmann ends the corpus below in a smaller octagon. He manages this transition by a frame construction of four oblong hexagons attached to the square. They originate in a square, open on one side, where a trapezium is connected. This foreshortens the bottom-most side of the hexagon. He closes the intermediate spaces formed by the trapezium by means of four triangles pointing upwards, thus completing the bottom end as an octagon. Cut-glass elements are fitted into the frame; their interplay with the coloured light reflexes in the cut-glass pendant chandelier elements introduces a random moment of movement into the austere frame construction. Hoffmann adds a balancing, almost exclusively circular, horizontal tendency to the decidedly vertical alignment of the pendant lamp. It is expressed in the wooden top plate fixed to the ceiling, in the hammered and conic metal plate mounted on the wooden plate, its horizontality emphasised by the rivets fitted in three concentric circles, and also in the two round end plates of the lantern corpus, and the metal discs attached to the middle, live cable.

The manner in which Hoffmann skilfully combines an abundance of aesthetic detail into a self-evident whole in this lamp manifests his genius as a designer. At the same time he remains true to his conviction, the idea that form and function form a logical unity of design.

CWD