Year

1905

Material

Silver, glass, various semi precious stones, mother-of-pearl, ivory, enamel, macassar ebony, veneer

Dimensions

H. 162,5 x W. 60,9 x D. 31,7 cm

Executed By

The Wiener Werkstätte (Model N° S1000)

Silversmiths

Adolf Erbrich and Josef Czech

Metalworkers

Franz Guggenbichler and Josef Holi

Marks

COC / AM / ROSEMARK / WW / VIENNESE DIANA’S HEAD

Kunstschau, Vienna, 1908

Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture, Design, MoMA, New-York, 1986

Viennese Silver: Modern Design, 1780-1918, Neue Galerie, New-York, 2003

MAK Archives,. Pictures: WWF 94-80-4, WWF 94-81-1, WWF 94-82-1, WWF 94-83-1, WWF 103-172-1, WWF 105-268-1, WWF 113-49-7 / Designs: WWE 174-3, WWE 174-1, WWE 174-2

The Studio, Band 52, 1911, P.196

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Vol.19, 1906-1907, P. 416-20, 443-56

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Vol.23, 1909, P. 168

“Austellung.” Die Werkkunst 3 (October 1907-September 1908), P. 319

Hussein-Arco, A., Gustav Klimt Und Die Kunstschau 1908, Munich, Belvedere, 2008, P. 448-49

Vienna 1900 – Klimt, Schiele, And Their Times, Ostfildern, Fondation Beyeler, 2010, P. 221

Alongside Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, Czeschka is one of the most eminent associates of the Wiener Werkstätte. He studied painting from 1894 to 1899 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. In the context of the Siebener Club (the Club of Seven) he came into contact with the later founding members of the Secession and committed himself to their ideology of the unity of the arts. It was chiefly Moser who kindled and subsequently fostered the young artist’s enthusiasm for the Viennese flat style in the graphic arts and painting. Thus by 1900 he was already a member of the Vienna Secession and in 1902 appointed assistant teacher for drawing at the unstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) of the Austrian Museum of Art and Industry. In 1904 he took over as head of the drawing and painting class until his departure for Hamburg in 1907, where he directed the specialist class for planar design and graphics and the artistic direction of the bookbinding workshop. It was Czeschka who recognized the young talent Oskar Kokoschka and enrolled him in his class, despite the resistance of his professorial colleagues.

The most important event for Czeschka’s further artistic career was his entry into the Wiener Werkstätte towards the end of 1905. Here he developed his talents as a draughtsman and attained grandiose achievements in all fields of the applied arts, most notably in the planar style. He was capable, like no other, of breathing life through his ornamental inventions into the surface area at his disposal. He developed his own unique ornamental style that derives from the graphic approach and plays with the opposite polarities of naturalism and abstraction. His work for the Wiener Werkstätte includes designs for metal objects, jewellery, furniture, graphics, textiles, embroidery, wall decorations, glass windows and works in leather. Although only for a short period, it occurred in the most creatively ambitious years of the Wiener Werkstätte, which saw the realization of a number of projects based on the gesamtkunstwerk, a synthesis of the arts. These included the interior design and furnishing of the Hochreith hunting lodge for Karl Wittgenstein, the home of Dr. Herrmann Wittgenstein, the interior design and furnishings of the Cabaret Fledermaus, and the building and furnishing of the Palais Stoclet. Czeschka’s name was associated with all these projects.

For Emperor Franz Josef’s Golden Jubilee, the Klimt Group organized the ‘Kunstschau’ (1908) as a large-scale show of the artistic achievements attained since the founding of the Secession.

In conjunction with Josef Hoffmann’s temporary exhibition building, the exhibition aimed to embody a synthesis of the arts. Room 50 of the exhibition was the representative room of the Wiener Werkstätte. Czeschka’s display cabinet, which the Wiener Werkstätte had worked on for two and a half years, was placed alone in its centre in a pre-eminent position. Its price, more than a Klimt portrait, was enormous – 25,000 kronen – the most expensive single object ever made by the Wiener Werkstätte. It was purchased by the Austrian industrial magnate Karl Wittgenstein (father of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein) for the salon of his palace in Vienna.

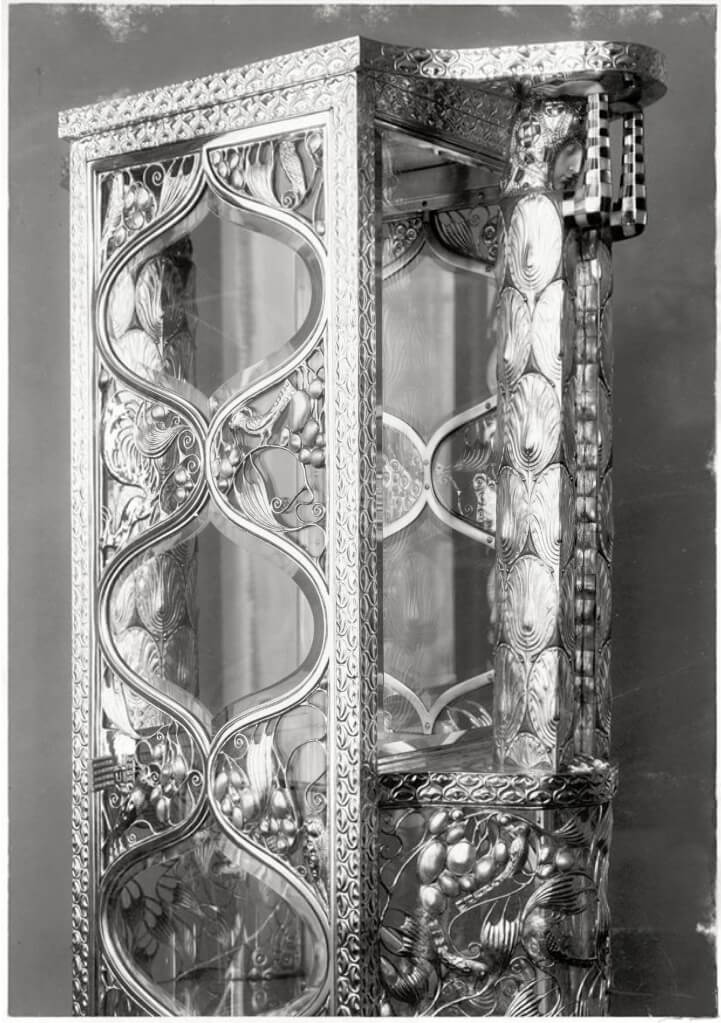

The display cabinet corpus is actually free-standing and fitted onto a base made of Makassar ebony, its ground plan formed of a rectangle with half-ovals set on the narrow sides, which flare out at the open ends. It is principally of hammered silver and bevelled and curved glass panes. Individual parts are decoratively accentuated with mother- of-pearl shells, semi-precious stones, enamel and ivory. The top is fashioned of onyx. Despite its elaborate surface decoration, the display cabinet corpus is clearly structured into single compartments by means of a decorative moulding with strong relief pattern, which adopts the shape of the bevelled glass panes. They are the two straight longitudinal sides of the cabinet into which the doors are set, as well as the two half-oval, flaring narrow sides, measuring three fifths of the corpus. The remaining top two fifths of the narrow sides are formed straight in continuation of the longitudinal sides. The resulting gradation of the narrow sides acts as a plinth on each for a caryatid, which together support the top. Their outline corresponds yet again to the larger dimension of the display cabinet’s base. This gives the impression of a closed, oblong furniture corpus, but allows the transparent central showcase part to attain its full effect as an autonomous vertical element. The overall composition of the display cabinet is not unlike a lace curtain, dominated by the subtle interplay of opaque versus transparent surfaces. In principle, transparency is provided solely in the longitudinal central part of the display cabinet, and this is restricted yet again to only five onion-shaped openings placed one above the other. The remaining areas of the long rectangle and the curved glass panes of the side areas are covered in a fantastical, transparent network of leaves, grape-like fruits, and all sorts of fauna.

The richly inventive vegetal network hides each of the five shelves inside the display cabinet so that the showpieces inside are framed as in a reliquary and appear to be in a state of flotation. Despite their solid execution, Czeschka manages to make the robes of the caryatids seem crocheted. He accomplishes this by filling in the intermediate spaces of the fabric pattern composed of shield-shaped leaves with blue enamel.

Czeschka’s design created in 1905 for the display cabinet occurred in the early years of the Wiener Werkstätte, when objects of unique individuality could be realized in consummately crafted execution and uninhibited by any financial considerations. Their extremely luxurious products were therefore dependent on the small class of the haute bourgeoisie that was open to the new artistic ideas of Viennese Modernism. In these terms, Czeschka’s display cabinet is an embodiment like hardly any other Wiener Werkstätte product of the creative enthusiasm of an extremely gifted young generation of artists, to whom the Wiener Werkstätte opened up the possibilities of living out their talents. Czeschka interprets the traditional theme of the ‘display cabinet’ anew and in the truest sense of the word makes a rare jewel out of it, one that was worthy of representing the Wiener Werkstätte for the Golden Jubilee of Emperor Franz Josef I.

CWD

Kunstschau, Vienna, 1908

Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture, Design, MoMA, New-York, 1986